Brutalism is architecture’s version of an acquired taste. It’s the kind of “love it or hate it” style that demands attention, unapologetically occupying space with its raw, unpolished aesthetic. Think massive, fortress-like slabs of concrete—tough, unwelcoming, and definitely not what you’d call “inviting.”

But in a world dominated by glass towers and hyper-curated interiors, Brutalism’s hard lines and uncompromising concrete surfaces feel oddly refreshing. For some, it’s a throwback to an era when architecture wasn’t about pleasing everyone. For others, it’s as inviting as a concrete slap in the face.

So, what’s the deal with Brutalism? And why is it making a comeback?

Brutalism: The Origins and Visionaries

Brutalism isn’t about brutality in the violent sense but rather about “béton brut”—French for “raw concrete.” The term was popularized by Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, who used exposed, unfinished concrete in works like Unité d’Habitation (1952) in Marseille.

This experimental residential complex, housing up to 1,600 people, included communal spaces and shops, embodying Le Corbusier’s vision of social housing. The project became a landmark in Brutalism, emphasizing large concrete forms, bold geometric shapes, and a minimalist, “anti-decorative” aesthetic.

The movement found its stride in the 1950s and ’60s as cities around the world faced rapid post-war expansion and urgent needs for affordable housing. In the UK, British architects Alison and Peter Smithson were influential champions of Brutalism, adapting Le Corbusier’s principles to reflect their own socially conscious approach.

Their Robin Hood Gardens housing complex in East London (completed in 1972) aimed to foster community, but the project ultimately fell into neglect and was mostly demolished by 2018. This transformation of a utopian vision into a symbol of failed social planning is central to Brutalism’s mixed legacy.

Another influential figure was Hungarian-born American architect Marcel Breuer, whose projects include The Whitney Museum of American Art (now The Met Breuer) in New York. His work brought Brutalism to institutional and cultural architecture, blending textured concrete with geometric, functional forms. Breuer’s buildings in the U.S. have made the Brutalist style synonymous with urban resilience.

From Utopian Dream to Concrete Nightmare

Brutalism began with big ideals: after WWII, cities urgently needed affordable housing and public spaces, and Brutalism offered a practical, cost-effective solution. It was a no-nonsense style for a world eager to rebuild. Governments, universities, and public institutions embraced it, and Brutalist architecture became a symbol of social progress and modern urban planning.

By the 1980s and ’90s, however, Brutalism began to fall out of favor. Initially seen as bold and progressive, Brutalist structures started to feel oppressive, especially as many public housing projects were neglected. This lack of maintenance took a toll on Brutalist buildings, and the raw concrete that once symbolized durability came to be associated with cold, inhuman spaces and urban decay. Critics began to view Brutalism as emblematic of modernist architecture’s failures, especially where social housing was concerned.

The Brutalist Revival: Instagram’s “Ugly” Aesthetic

Here’s the thing about Brutalism: it might look like an eyesore to some, but it photographs like a dream. Scroll through Instagram, Pinterest, or architectural magazines, and Brutalism’s stark aesthetic is everywhere. Its monolithic, monochromatic presence feels fresh in a digital age obsessed with minimalism and clean lines.

In a time of hyper-curated, polished visuals, Brutalism’s raw honesty resonates. For many, its unapologetic concrete surfaces are like a no-makeup selfie—raw and real. Brutalism’s unpolished authenticity appeals to those seeking a grounded, unfiltered aesthetic.

The Digital Generation’s Concrete Fixation?

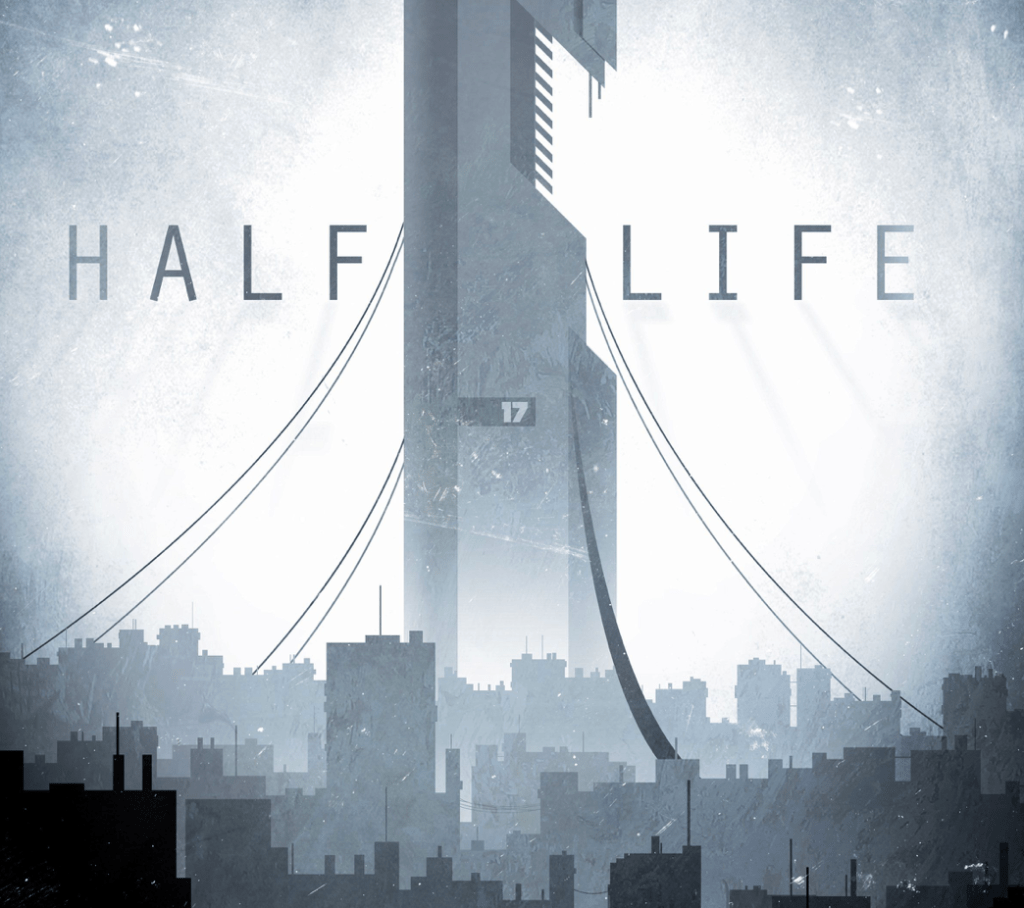

Here’s where things get interesting: Brutalism, an analog relic, somehow looks surprisingly futuristic on a digital screen. The heavy lines, imposing shapes, and unapologetically raw materials have made their way into video games, fashion, and art. Gamers recognize Brutalist-inspired environments in titles like Half-Life 2 and Control, which use the style’s unyielding forms to create psychologically intense spaces. These concrete worlds aren’t exactly warm, but that’s precisely why they stick with you.

Brutalism has become a cultural meme of sorts—a reference point for spaces that feel grounded, even as they reflect a digital world that can be detached and surreal. Standing next to a Brutalist building makes you feel small in the best way, its heavy, unfiltered form reminding you of what it’s like to feel something physical and lasting.

Neo-Brutalism: The Modern Remix

As with any style that refuses to die, Brutalism is being reinterpreted for the 21st century. Enter “neo-Brutalism,” a movement that retains the aesthetic heaviness of Brutalism while blending in sustainability and contemporary design practices. Architects today are exploring Brutalist-inspired designs with eco-conscious materials, maximizing natural light, and incorporating green spaces.

For example, Boston’s City Hall, one of America’s most famous Brutalist structures, is undergoing renovations to improve functionality while preserving its Brutalist identity. In Japan, Brutalism is reemerging with a modern twist as architects explore concrete’s versatility in modular and green spaces. In São Paulo, Brazil, Brutalist-inspired projects like Lina Bo Bardi’s SESC Pompeia have become cultural hubs, showing that Brutalism can adapt to vibrant, active spaces.

Brutalism Isn’t Going Anywhere

Brutalism isn’t just a style; it’s a statement on the purpose and impact of architecture. Should buildings make us feel comfortable, or should they challenge us? Brutalism doesn’t seek to please or blend in; it asks us to confront our expectations. Brutalist buildings are memorable, celebrated for their rawness and defiance.

Seventy years later, people still debate Brutalism’s value. This endurance alone proves that Brutalism is more than just a design choice—it’s an architectural philosophy. Whether you see these structures as ugly or iconic, Brutalism isn’t going anywhere. It’s here to stay, reminding us that architecture can be as raw and unapologetic as life itself.

Concrete Love, Concrete Hate

In a world dominated by glass facades and minimalist interiors, Brutalism stands out. Some people will always view these buildings as ugly relics of a failed social experiment. But to Brutalism’s admirers, these concrete giants represent something deeper: a refusal to conform.

Whether they’re left to decay or carefully restored, Brutalist buildings remain a powerful presence in our cities. They don’t care if they’re beautiful or ugly. They simply exist, unapologetic and unyielding—a testament to architecture’s power to provoke and endure.

Brutalism’s appeal isn’t for everyone—and that’s precisely the point. It’s architecture that demands a reaction, asking you to confront your expectations and find beauty where you least expect it.

Go Deeper and Check out These Iconic Brutalist Buildings Across the Globe

Brutalism wasn’t confined to any one country. It spread around the world, leaving iconic structures across continents:

- United States: Boston City Hall by Kallmann, McKinnell, and Knowles (1968) is a bold civic landmark, known for its stark concrete forms and fortress-like design. Another example is Geisel Library at UC San Diego, designed by William Pereira in 1970, with a futuristic, cantilevered look.

- Japan: The Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Tower (1967) by Kenzo Tange represents a unique adaptation of Brutalism in a modular form. Tange, an influential figure in post-war Japanese architecture, incorporated Brutalist elements with Japan’s rebuilding ethos, bringing a sense of innovation to the style.

- France: Beyond Unité d’Habitation, Brutalism’s impact on religious architecture can be seen in Église Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay by Claude Parent and Paul Virilio (1966), a fortress-like structure with a stark, angular concrete facade.

- Latin America: The National Library of Argentina by Clorindo Testa in Buenos Aires, completed between 1961 and 1992, fuses Brutalist ideals with local architectural identity. Its layered concrete forms and expressive shapes make it one of Argentina’s most recognized Brutalist buildings.

- Eastern Europe: The Ministry of Highways in Tbilisi, Georgia (1975), designed by George Chakhava, is an iconic example of Eastern European Brutalism with stacked concrete forms that appear suspended, reflecting the region’s architectural distinctiveness.

- United Kingdom: In addition to Robin Hood Gardens, The Barbican Estate in London (designed by Chamberlin, Powell, and Bon, completed in the 1970s) is a Brutalist megastructure with housing, shops, and cultural venues, embodying the ambition to create comprehensive urban living spaces.

- Australia: The Sirius Building in Sydney (1979) by Tao Gofers was originally intended as public housing. Its geometric, modular structure has since become a cultural landmark, though debates over its preservation continue.